Definitions and basic concepts

What is DevOps?

Before we get started with Docker let's lay the groundwork for learning the right mindset. Defining DevOps is not a trivial task but the term itself consists of two parts, Dev and Ops. Dev refers to the development of software and Ops to operations. Simple definition for DevOps would be that it means the release, configuring, and monitoring of software is in the hands of the very people who develop it.

A more formal definition is offered by Jabbari et al.: "DevOps is a development methodology aimed at bridging the gap between Development and Operations, emphasizing communication and collaboration, continuous integration, quality assurance and delivery with automated deployment utilizing a set of development practices".

Image of DevOps toolchain by Kharnagy from wikipedia

Sometimes DevOps is regarded as a role that one person or a team can fill. Here's some external motivation to learn DevOps skills: Salary by Developer Type in StackOverflow survey. You will not become a DevOps specialist solely from this course, but you will get the skills to help you navigate in the increasingly containerized world.

During this course we will focus mainly on the packaging, releasing and configuring of the applications. You will not be asked to plan or create new software. We will go over Docker and a few technologies that you may see in your daily life, these include e.g. Redis and Postgres. See StackOverflow survey on how closely they correlate these technologies.

What is Docker?

"Docker is a set of platform as a service (PaaS) products that use OS-level virtualization to deliver software in packages called containers." - from Wikipedia.

So stripping the jargon we get two definitions:

- Docker is a set of tools to deliver software in containers.

- Containers are packages of software.

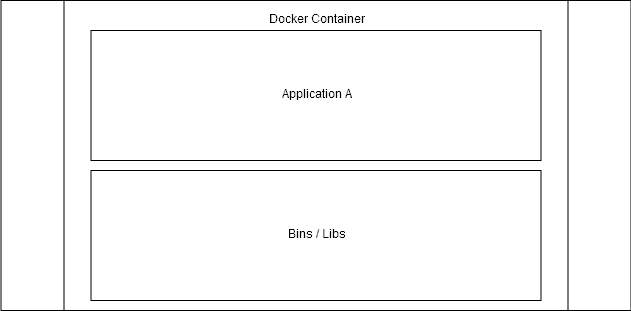

The above image illustrates how containers include the application and its dependencies. These containers are isolated so that they don't interfere with each other or the software running outside of the containers. In case you need to interact with them or enable interactions between them, Docker offers tools to do so.

Benefits from containers

Containers package applications. Sounds simple, right? To illustrate the potential benefits let's talk about different scenarios.

Scenario 1: Works on my machine

Let's first take a closer look into what happens in web development without containers following the chain above starting from "Plan".

First you plan an application. Then your team of 1-n developers create the software. It works on your computer. It may even go through a testing pipeline working perfectly. You send it to the server and...

...it does not work.

This is known as the "works on my machine" problem. The only way to solve this is by finding out what in tarnation the developer had installed on their machine that made the application work.

Containers solve this problem by allowing the developer to personally run the application inside a container, which then includes all of the dependencies required for the app to work.

- You may still occasionally hear about "works in my container" issues - these are often just usage errors.

Scenario 2: Isolated environments

You have 5 different Python applications. You need to deploy them to a server that already has an application requiring Python 2.7 and of course none of your applications are 2.7. What do you do?

Since containers package the software with all of its dependencies, you package the existing app and all 5 new ones with their respective python versions and that's it.

I can only imagine the disaster that would result if you try to run them side by side on the same machine without isolating the environments. It sounds more like a time bomb. Sometimes different parts of a system may change over time, possibly leading to the application not working. These changes may be anything from an operating system update to changes in dependencies.

Scenario 3: Development

You are brought into a dev team. They run a web app that uses other services when running: a postgres database, mongodb, redis and a number of others. Simple enough, you install whatever is required to run the application and all of the applications that it depends on...

What a headache to start installing and then managing the development databases on your own machine.

Thankfully, by the time you are told to do that you are already a docker expert. With one command you get an isolated application, like postgres or mongo, running in your machine.

Scenario 4: Scaling

Starting and stopping a docker container has little overhead. But when you run your own Netflix or Facebook, you want to meet the changing demand. With some advanced tooling that we will learn about in parts 2 and 3, we can spin up multiple containers instantly and load balance traffic between them.

Container orchestration will be discussed in parts 2 and 3. But the simplest example: what happens when one application dies? The orchestration system notices it, splits traffic between the working replicas, and spins up a new container to replace the dead one.

Virtual machines

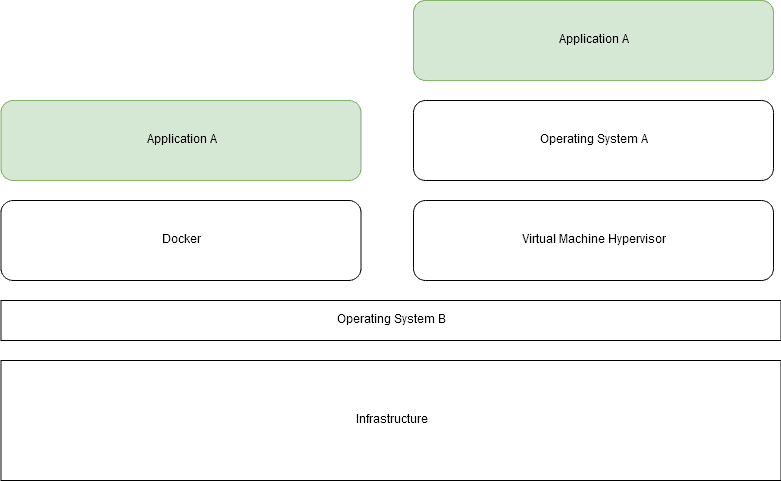

Isn't there already a solution for this? Virtual Machines are not the same as Containers - they solve different problems. We will not be looking into Virtual Machines in this course. However, here's a diagram to give you a rough idea of the difference.

The difference between a virtual machine and docker solutions after moving Application A to an incompatible system "Operating System B". Running software on top of containers is almost as efficient as running it "natively" outside containers, at least when compared to virtual machines.

So containers have a direct access to your own Operating Systems kernel and resources. The resource usage overhead of using containers is minimized, as the applications behave as if there were no extra layers. As Docker is using Linux kernels, Mac and Windows can't run it without a few hoops and each have their own solutions on how to run Docker.

Running containers

You already have Docker installed so let's run our first container!

The hello-world is a simple application that outputs "Hello from Docker!" and some additional info.

Simply run docker container run hello-world, the output will be the following:

$ docker container run hello-world

Unable to find image 'hello-world:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

b8dfde127a29: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:308866a43596e83578c7dfa15e27a73011bdd402185a84c5cd7f32a88b501a24

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

To generate this message, Docker took the following steps:

1. The Docker client contacted the Docker daemon.

2. The Docker daemon pulled the "hello-world" image from the Docker Hub.

(amd64)

3. The Docker daemon created a new container from that image which runs the

executable that produces the output you are currently reading.

4. The Docker daemon streamed that output to the Docker client, which sent it

to your terminal.

To try something more ambitious, you can run an Ubuntu container with:

$ docker run -it ubuntu bash

Share images, automate workflows, and more with a free Docker ID:

https://hub.docker.com/

For more examples and ideas, visit:

https://docs.docker.com/get-started/If you already ran hello-world previously it will skip the first 5 lines. The first 5 lines tell that an image "hello-world:latest" wasn't found and it was downloaded. Try it again:

$ docker container run hello-world

Hello from Docker!

...It found the image locally so it skipped right to running the hello-world.

So that's an image?

Image and containers

Since we already know what containers are it's easier to explain images through them: Containers are instances of images. A basic mistake is to confuse images and containers.

Cooking metaphor:

- Image is pre-cooked, frozen treat.

- Container is the delicious treat.

With the cooking metaphor, the difficult task is creating the frozen treat while warming it up is relatively easy. Images require some work and knowledge to be created, but when you know how to create images you can leverage the power of containers in your own projects.

Image

A Docker image is a file. An image never changes; you can not edit an existing file. Creating a new image happens by starting from a base image and adding new layers to it. We will talk about layers later, but you should think of images as immutable, they can not be changed after they are created.

List all your images with docker image ls

$ docker image ls

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

hello-world latest d1165f221234 9 days ago 13.3kBContainers are created from images, so when we ran hello-world twice we downloaded one image and created two of them from the single image.

Well then, if images are used to create containers, where do images come from? This image file is built from an instructional file named Dockerfile that is parsed when you run docker image build.

Dockerfile is a file named Dockerfile, that looks something like this

Dockerfile

FROM <image>:<tag>

RUN <install some dependencies>

CMD <command that is executed on `docker container run`>and is the instruction set for building an image. We will look into Dockerfiles later when we get to build our own image.

If we go back to the cooking metaphor, Dockerfile is the recipe.

Container

Containers only contain that which is required to execute an application; and you can start, stop and interact with them. They are isolated environments in the host machine with the ability to interact with each other and the host machine itself via defined methods (TCP/UDP).

List all your containers with docker container ls

$ docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMESWithout -a flag it will only print running containers. The hello-worlds we ran already exited.

$ docker container ls -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

b7a53260b513 hello-world "/hello" 5 minutes ago Exited (0) 5 minutes ago brave_bhabha

1cd4cb01482d hello-world "/hello" 8 minutes ago Exited (0) 8 minutes ago vibrant_bellDocker CLI basics

We are using the command line to interact with the "Docker Engine" that is made up of 3 parts: CLI, a REST API and docker daemon. When you run a command, e.g. docker container run, behind the scenes the client sends a request through the REST API to the docker daemon which takes care of images, containers and other resources.

You can read the docs for more information. But even though you will find over 50 commands in the documentation, only a handful of them is needed for general use. There's a list of the most commonly used basic commands at the end of this section.

One of them is already familiar: docker container run <image>, which instructs daemon to create a container from the image and downloading the image if it is not available.

Let's remove the image since we will not need it anymore, docker image rm hello-world sounds about right. However, this should fail with the following error:

$ docker image rm hello-world

Error response from daemon: conflict: unable to remove repository reference "hello-world" (must force) - container <container ID> is using its referenced image <image ID>This means that a container that was created from the image hello-world still exists and that removing hello-world could have consequences. So before removing images, you should have the referencing container removed first. Forcing is usually a bad idea, especially as we are still learning.

Run docker container ls -a to list all containers again.

$ docker container ls -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

b7a53260b513 hello-world "/hello" 35 minutes ago Exited (0) 35 minutes ago brave_bhabha

1cd4cb01482d hello-world "/hello" 41 minutes ago Exited (0) 41 minutes ago vibrant_bellNotice that containers have a CONTAINER ID and NAME. The names are currently autogenerated. When we have a lot of different containers, we can use grep (or another similar utility) to filter the list:

$ docker container ls -a | grep hello-worldLet's remove the container with docker container rm command. It accepts a container's name or ID as its arguments.

Notice that the command also works with the first few characters of an ID. For example, if a container's ID is 3d4bab29dd67, you can use docker container rm 3d to delete it. Using the shorthand for the ID will not delete multiple containers, so if you have two IDs starting with 3d, a warning will be printed, and neither will be deleted. You can also use multiple arguments: docker container rm id1 id2 id3

If you have hundreds of stopped containers and you wish to delete them all, you should use docker container prune. Prune can also be used to remove "dangling" images with docker image prune. Dangling images are images that do not have a name and are not used. They can be created manually and are automatically generated during build. Removing them just saves some space.

And finally you can use docker system prune to clear almost everything. We aren't yet familiar with the exceptions that docker system prune does not remove.

After removing all of the hello-world containers, run docker image rm hello-world to delete the image. You can use docker image ls to confirm that the image is not listed.

You can also use the image pull command to download images without running them: docker image pull hello-world

Let's try starting a new container:

$ docker container run nginxNotice how the command line appears to freeze after pulling and starting the container. This is because Nginx is now running in the current terminal, blocking the input. You can observe this with docker container ls from another terminal. Let's exit by pressing control + c and try again with the -d flag.

$ docker container run -d nginx

c7749cf989f61353c1d433466d9ed6c45458291106e8131391af972c287fb0e5The -d flag starts a container detached, meaning that it runs in the background. The container can be seen with

$ docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

c7749cf989f6 nginx "nginx -g 'daemon of…" 35 seconds ago Up 34 seconds 80/tcp blissful_wrightNow if we try to remove it, it will fail:

$ docker container rm blissful_wright

Error response from daemon: You cannot remove a running container c7749cf989f61353c1d433466d9ed6c45458291106e8131391af972c287fb0e5. Stop the container before attempting removal or force removeWe should first stop the container using docker container stop blissful_wright, and then use rm.

Forcing is also a possibility and we can use docker container rm --force blissful_wright safely in this case. Again for both of them instead of name we could have used the ID or parts of it, e.g. c77.

It's common for the docker daemon to become clogged over time with old images and containers.

Most used commands

| command | explain | shorthand |

|---|---|---|

docker image ls | Lists all images | docker images |

docker image rm <image> | Removes an image | docker rmi |

docker image pull <image> | Pulls image from a docker registry | docker pull |

docker container ls -a | Lists all containers | docker ps -a |

docker container run <image> | Runs a container from an image | docker run |

docker container rm <container> | Removes a container | docker rm |

docker container stop <container> | Stops a container | docker stop |

docker container exec <container> | Executes a command inside the container | docker exec |

For all of them container can be either the container id or the container name. Same for images. In the future we may use the shorthands in the material.

Some of the shorthands are legacy version of doing the same thing. You can use either.